Archives

There are two appropriate dates in the calendar for miraculous solutions: the solstices of the year.

On this occasion we shall refer to the summer solstice, or what is the same, the night before St. John’s Day, associated to having great potential for extraordinary solutions which exceeded all natural logic and order.

One of the usual rites of that night aimed at curing herniated children. They were kids whose guts were partially eviscerated by a tear of the peritoneal membrane. They usually had a lump in the lower abdomen, often in the groin, where the thigh joins the lower belly. This injury could bring very serious consequences, including the possibility of death.

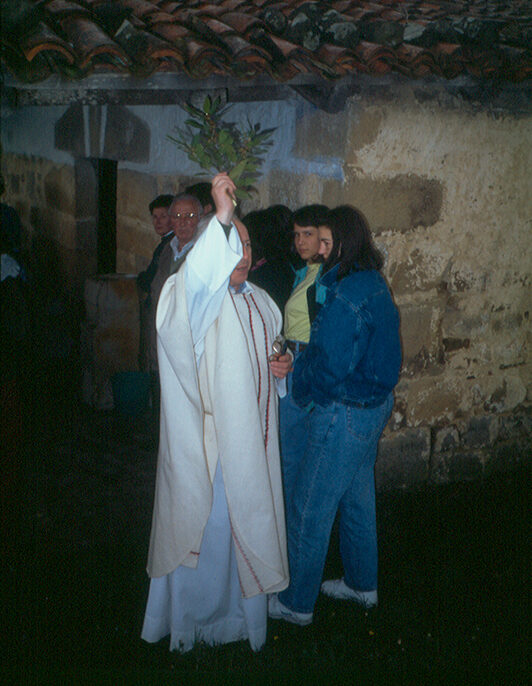

Preparing branches of bay in Muxika, 2014. Photographer: Igone Etxebarria. Labayru Fundazioa Photography Archive.

Different cultures have had a close relationship with the trees, bushes or plants in their natural surroundings; those plants have been depicted in their customary symbols, used in their cooking and to make medicines, or as models and motifs to inspire their artistic creations or to decorate their craftwork. They include the bay branch (ereinotza edo erramua) which is at its most splendid at the start of spring or ready to be blessed and exhibited or decorated on Palm Sunday. That is the religious commemoration that symbolises the triumphal biblical entry of Jesus Christ on the back of a donkey into Jerusalem; he is welcomed in the Mediterranean area by crowds waving olive and palm branches. However, it is the bay tree in the Atlantic area – known for its supposed and possible properties, the protection it offers against lightning, and as a condiment to flavour food – that has lasted down through the generations in the collective memory of our traditional culture. It has been used by Catholic priests as a hyssop (along with the blessed salt and water) for a myriad of blessings of people, animals, sown fields or rough water, estates and communities.

Blessed small branches of bay have been placed as personal protection on the crucifix over the bedhead or on the home stoup in each bedroom; a small piece of its perennial leaf was sometimes kept to make chams (kuttunak) or to place them between the pages of the devotional books. Homes or mountain huts, vessels or their dwellers are also protected by placing a small branch on the door or lintel, the balcony, the entrance to the stables or over the bridge of the boats. After being blessed on Palm Sunday (in some cases, the blessing takes place during the May Cross festivities), the hazelnut crosses (txolak edo galtzuek) and decorated with bay are erected in the different fields, and are replaced by the old monstrances that will be burnt on the bonfires on Midsummers Eve.

Spring is when boats set sail to sea and fields are sown; it is also the time of possible agricultural pests, livestock disease and is not free from extreme weather events (frost, hail or hailstones, droughts or sudden and devastating storms). In the past, such events would be synonymous with lack of resources, famine, epidemics, death and devastation. On the other hand, the use of this bush in traditional curative medicine is obvious and appropriate for different conditions. It is even regularly used as the symbol to announce the start of tasting a barrel of cider or of txakoli wine, by placing a branch in the establishment or home, along with several small bay branches (branques) near to the place where it is produced and drunk. Then we cannot forget that when the workers complete the structure of a building, they place a branch of bay at the highest point to indicate the work is finished and to protect the construction.

People in the past clearly held fast to the symbolic and self-serving interpretation of the animals, plants and minerals to be found around them. They were given a ritual or mythical meaning, according to the needs that emerged in the course of their daily or community life, and then became part of the folklore that became part of the customs passed on by word of mouth or in writing. This process of weighing plants, such as the bay, against adversities, possible dangers and elicited fears is a constant in all cultures.

Josu Larrinaga Zugadi – Sociologist

Anthropologists, ethnologists, ethnographers, folklorists, linguists and historians are just some of the people who have worked on preparing systems to classify and catalogue the plethora of festivities and events on the annual calendar, both in the past and in the present.

While not overlooking the rituality, authenticity, traditionality – along with many other terms ending in ‘-ity’ –, the main contribution should, undeniably, be focused on the recreational diversity, seasonality and timelessness, the historical context, the spatial spheres, the social and cultural aspects, the context, etc.

The most direct relationship – and undoubtedly of vital importance – between nature, (in its plant inanimate aspect) and the human being, in these latitudes and leaving aside the information that the virtual and audiovisual media overwhelms us with every day, is practically part of the past, but we are aware that it still remains and how it has managed to adapt.

Let us start with flowers, such as those of St. John that were arranged – along with onions, corn, wheat, cherries and herbs – into a bunch or sortie to be blessed in the church and, later, placed in the door or window of the house on the saint’s day. We now very rarely see those bunches and in a few more the flower of the thistle or eguzki lore. The fate of the custom of lighting wheat sheaves and going through private fields chanting a spell for a good crop has been worse, as it has fallen out of use.