Basque ethnography at a glance

Los de abril para mí, los de mayo para el amo y los de junio para ninguno ‘April spears for me, May spears for the master, and June spears for no one’ goes the saying which best describes the optimal times to harvest and consume this spring vegetable: namely, asparagus.

Esparragoa, zainzuria or frantses-porrua is a herbaceous plant, with highly branched aerial stems, and an underground roots and buds system, often referred to as ‘crown’ or ‘claw’. And edible, straight and white spears grow from emerging young shoots.

On 15 May we celebrate the feast of St Isidore, or Isidore the Farmer, widely venerated as patron saint of farmers. As it happens, farm folks have customarily interceded with him to ask for protection of their crops.

More than a handful of towns and villages in Bizkaia (Derio, Getxo, Zeanuri, Murueta…) hold their patron saint festivities around this time. In Getxo and Zeanuri, for instance, livestock fairs and competitions, as well as oxen tests, have a centuries-long tradition and continue to attract large crowds.

Flag waving before the image of St James. Garai (Bizkaia), 2013. Photo credit: Emilio Xabier Dueñas.

Nothing but simple rags with a lost function for some, unique rewards for impressive feats accomplished for others, and a symbol of identity for an important part of society. Be that as it might, the banner, the standard, the flag… are often insignia and fabrics loaded with devotion, fanaticism or honour, straddling boundaries —sports, religion, politics, patriotism, or folklore—, and even seeking to differentiate social status.

On more than one occasion we have been able to observe how in some European countries, as well as in territories close to Euskal Herria, in sumptuous or festive acts, flags are waved: whether defending a military origin or as a ritual with historic roots in the uprising of the people against the oppressive feudal power.

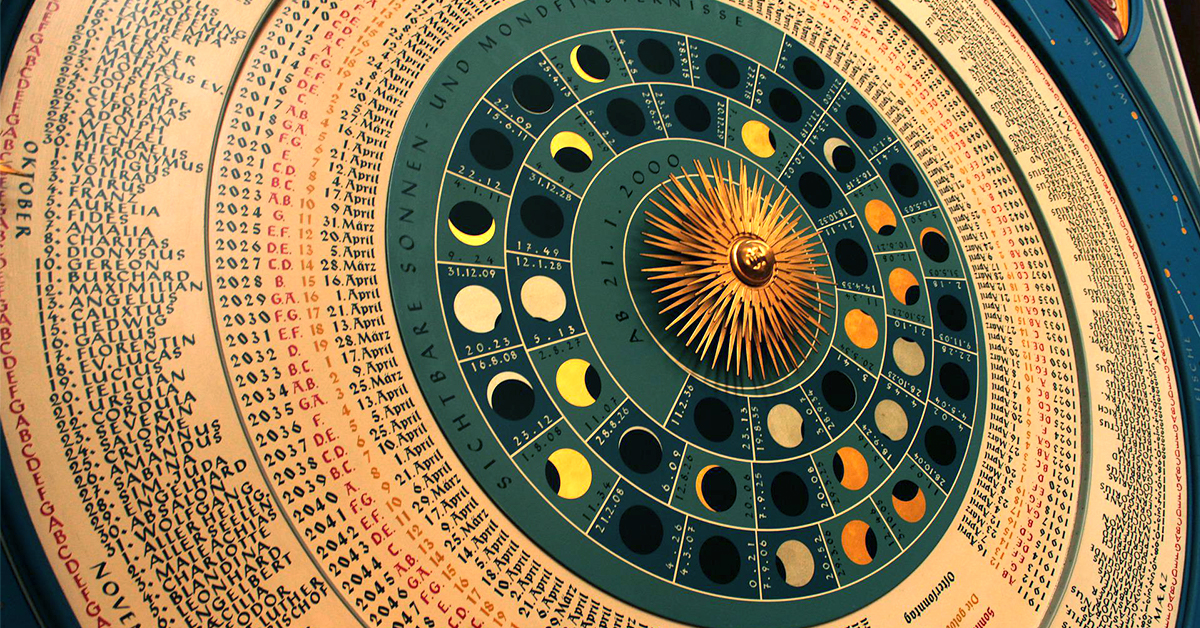

Regarding the term kuarta tenpora, most commonly used among us to designate these four sets of three days, and contrary to what it might seem, it does not allude to the fact that such celebrations took place four times a year, but comes from Latin feria quarta. In origin, that is to say, in Roman times, and from a religious point of view, ember days —the mentioned kuarta tenporak in Basque— were quarterly periods prescribed by the Church for fasting and prayer. As for the name feria quarta, it provided a means to designate a certain day of the week in Latin: starting from Sunday, Monday would be the feria secunda; Tuesday the feria tertia, feria quarta thus being the denomination of Wednesday received by the Church in Latin. On Epiphany, 6 January, from the pulpit of the parish church, the proclamation of the most important religious feasts of the liturgical year would be read. And quatuor tempora days were also announced, specifying the initial day, Wednesday, beginning with the opening formula Feria quarta tempora erit…, and subsequently giving the dates for each fasting and prayer day.