Basque ethnography at a glance

Panoramic view of common pastures in La Calera del Prado. Valley of Carranza (Bizkaia), 2008. Miguel Sabino Díaz.

In the Valley of Carranza (Bizkaia) the best common wood-pastures located in the lowlands within close proximity to populations were formerly known as boheriza. The terms boriza and voeriza were also registered on 18th and 19th-century public record. (more…)

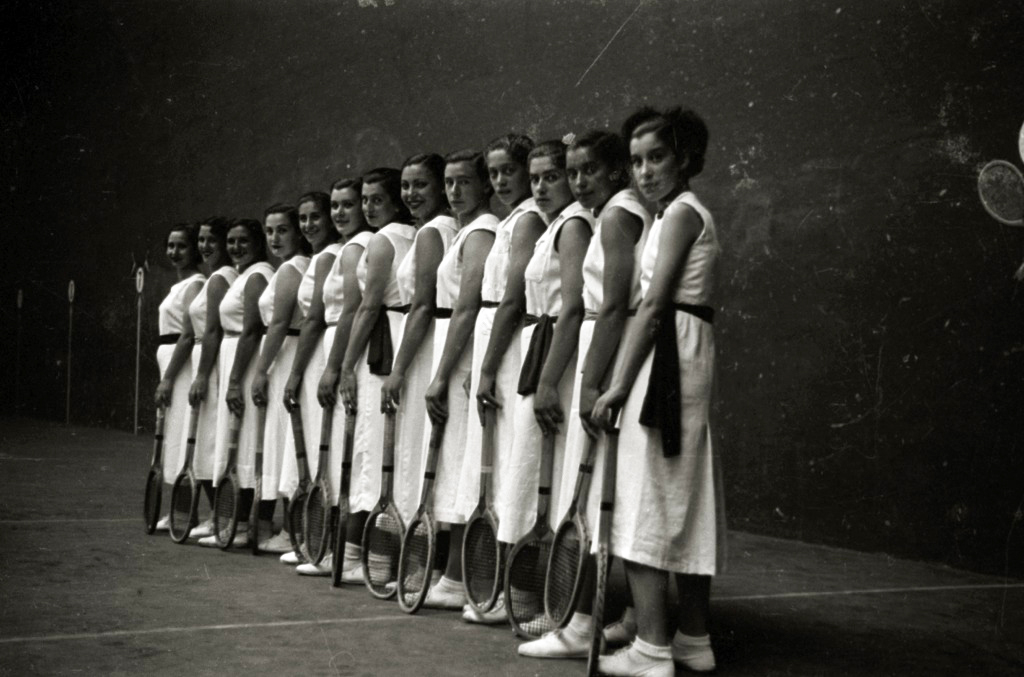

Group of women racket players. Gros Fronton in Donostia, 1938. Pascual Marín. Kutxateka.

Some time ago the Euskal Herria Museum in Gernika presented the exhibition “Emakumea eta Euskal Pilota. Mujer y Pelota Vasca [Woman and Basque pelota]”, which has been shown in different locations in Bizkaia. It is an interesting research work intended to rethink the role of women in Basque pelota, or pilota, by reminding us of the forgotten presence of female racket players, or raquetistas, in ball courts worldwide throughout the 20th century while giving due recognition to their contribution. (more…)

Scarecrow. Azkoitia (Gipuzkoa), 2018. Idoia Tolosa. Labayru Fundazioa Photographic Archive.

Placed in open cultivated fields, vineyards and fruit groves, homemade humanoid scarecrows have been a common way to protect freshly broadcast seed, growing crops and fruit harvests from birds, though in recent times are being partly substituted by more effective methods. They have been mostly used in fields of wheat and maize, and still guard young onion plants, turnip intended for seed, broad beans and green peas with filled pods… Several dummies might be needed for large areas. In fields of crops they are installed in June, and in vineyards in September; fruit trees with abundant ripe fruit, especially cherry trees, are also protected. Common names for ‘bird scarers’ are espantapájaros, in Spanish, and txorimaloak, txori-jagoleak or kusoak, among others, in Basque. (more…)

Juan Oleaga, the blacksmith. Maruri-Jatabe (Bizkaia), 1999. Mikel Martínez. Labayru Fundazioa Photographic Archive.

My first knowledge of the art and trade of the blacksmith (errementaria, in Basque) came in childhood. I was no more than nine or ten years of age when, on a Saturday morning, my mother tasked me with a most peculiar errand: I was to help a neighbour walk a cow to the blacksmith’s in Maruri-Jatabe, a nearby locality some nine kilometres from Urduliz (Bizkaia), my native village. I was asked to follow from behind with a stick in my hands and herd the animal should it stop moving or not keep up pace, an apparently straightforward task. But what started out as an excursion —I was rewarded with a small package of assorted biscuits for the road, much to my delight— became a never-ending and exhausting day. (more…)