Basque ethnography at a glance

Ascension Day was a significant reference in the calendar of our ancestors.

According to Christianity, it is celebrated forty days after Easter Sunday and commemorates the ascension of Jesus Christ to heaven in the presence of his disciples.

Transferred to the profane environment, the Ascension marks the end of a specific period, which begins with the equinox and the beginning of spring and shows us the moment in which meadows, forests and crop fields show the moment of greatest prosperity. Furthermore, it was planting time.

7 amazing words

In any language we can find incredible words, because the words themselves are original, expressive, changing, capricious… and among those oral flowers there are of many ages, sizes, appearance, colors and meanings. How can we not be amazed, thus, contemplating some of those wonderful pieces that yesterday and today in different places human intelligence and creativity have been produced! Nowadays it has become fashionable to show emblematic words from different languages on social networks, for people’s enjoyment. The idea is really good. But in these reels or short videos, false or invented etymologies are often given, due to the obsession with dazzling people. That is not our intention. Here we will present seven words or expressions from Basque, which have some particularity that makes them special. We use some of them naturally in our daily live, sometimes without paying attention to their intrinsic value or their beauty. Others we use less frequently, despite knowing them. And some of them may even be on the verge of extinction, having been displaced from use by new words and/or alterations in their meaning. In any case, all of them are part of our language and we are not going to give them up! On the contrary. It is a real pleasure to be able to display them on the counter, so that, on the one hand, we realize their value, and on the other, we feel encouraged to use them in the future.

Ezpata Dantza (sword dance) for Corpus Christi performed by Goizaldi Dantza Taldea (Donostia, 06/06/1985). Photo: E. X. Dueñas

“Traditional” and/or “Basque” is one way of pigeonholing the dance performed by groups here. That has not always been the case and that is also true of how they are performed, however hard people champion the authenticity and, therefore, the inflexibility of steps and shapes down through the centuries.

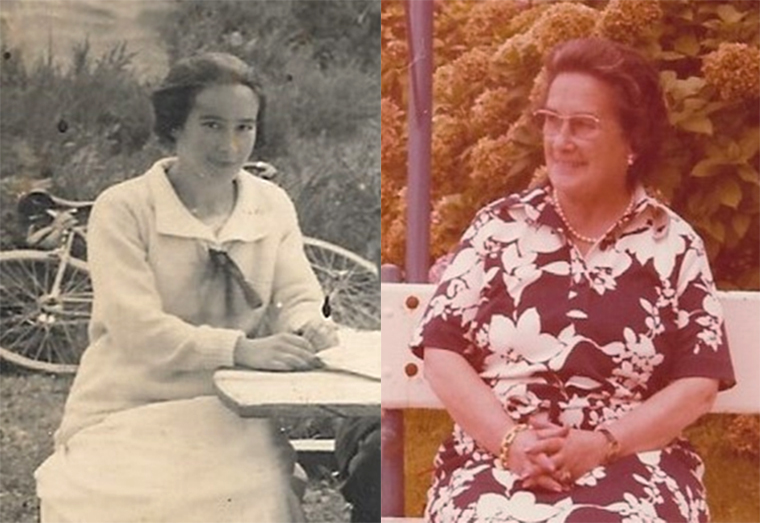

On 14 March, the book that the author Jule Gabilondo Maite wrote in Saint-Jean-de-Luz (Labourd) between 1937 and 1938 was presented in the cultural centre in the Torrebillela tower house (Mungia).

Jule Gabilondo Arruza-Zabala was born in Mungia on 29 January 1902. Her father, Juan Gabilondo Azurmendi, a doctor, was from Zegama (Gipuzkoa) and her mother, Leonor Arruza-Zabala Etxaburu, from Gueñes (Bizkaia). Her maternal grandfather, Raimundo Arruza-Zabala, was born in Mungia, but married in the town of Gueñes and returned to his birthplace with his family several years later. (more…)