Basque ethnography at a glance

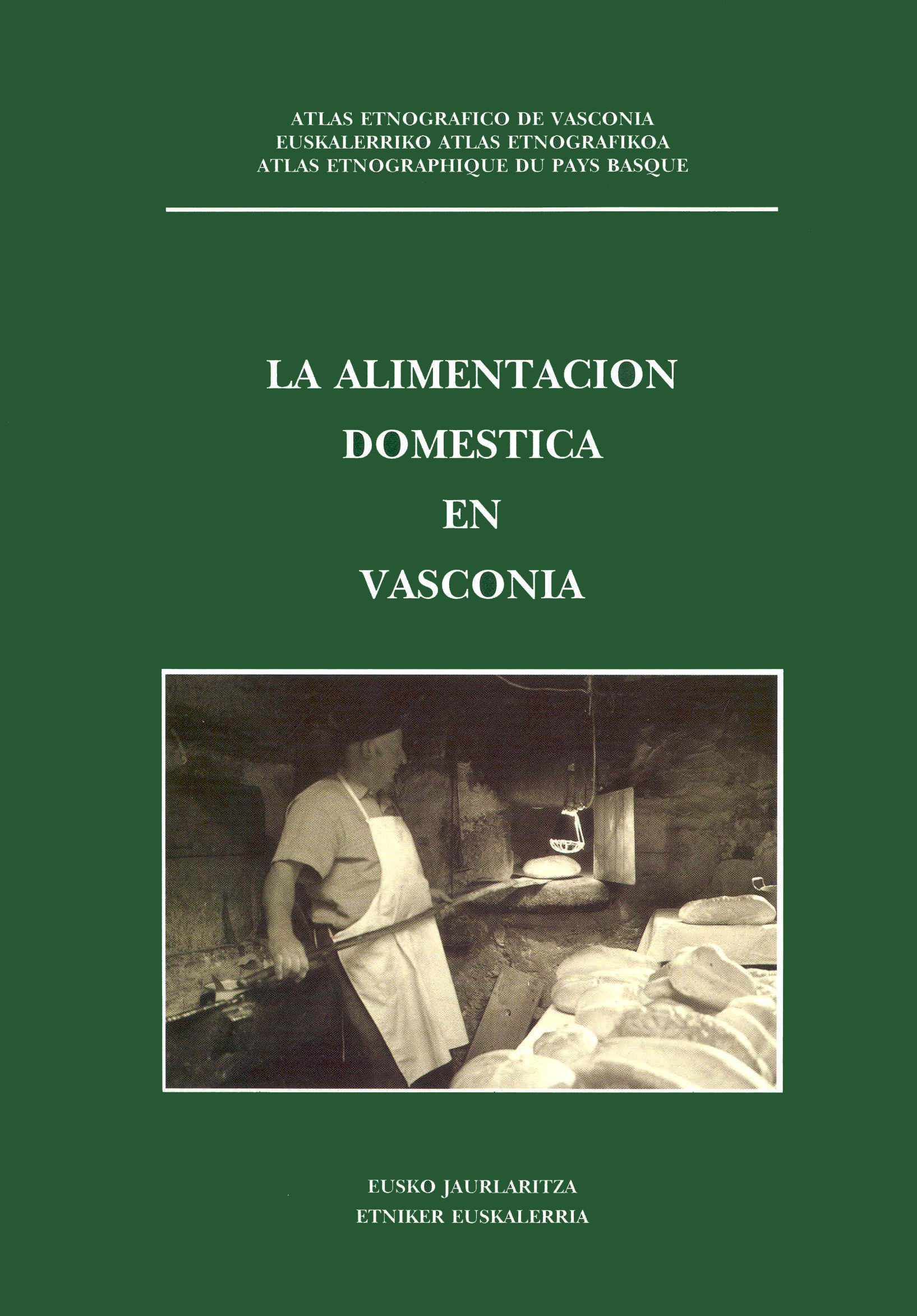

First volume of the Ethnographic Atlas of the Basque Country.

In the realm of knowledge ethnography (with a small e) is a minor field of study compared to Anthropology, for instance, which, shall we say, does not carry much weight in the arena of social sciences either, nor science in general for that matter. (more…)

Freshly cut saffron milk caps in Laza (Roncal Valley). Pablo M. Orduna.

Before permanently settling down, a nomadic hunter-gatherer system of living and working prevailed in many communities. In the Pyrenees seasonal migratory movement of transhumant herders with their livestock from the bottom of the valleys to mountain heights and from there to the banks of Ebro River still remains as a fading vestige of a former way of life. Yet a number of activities, formerly complementary to the acquisition of necessary food resources, have gained increasing interest, such is the case of hunting and wild mushroom picking, which now return with a renewed focus in terms of leisure and recreation. The impact of mushroom picking alone has indeed been significant, for it has attracted hordes of enthusiasts, a means of financial support to foster local development on the one hand, but potentially damaging to the natural and cultural landscape of the region on the other. (more…)

Sheep-breeding was in full swing in the last decades of the 19th century. A newly created Ministry of Agriculture was responsible for developing the sector. It was then that the identification of local breeds started. (more…)

Corporation members from Arrastaria in procession to Our Lady of Old Sanctuary. Urduña (Bizkaia), 2014. Labayru Fundazioa Photographic Archive.

8 May is an eventful day in Urduña. The feast is popularly known as ochomayos. Locals commemorate the renewal of the vow made to Our Lady of Old, their patroness, back in the 17th century.

On 9 May all attention moves to the Arrastaria Valley. The valley belongs now to the municipality of Amurrio (Álava) and comprises the villages of Tertanga, Délica, Artomaña and Aloria. (more…)