Basque ethnography at a glance

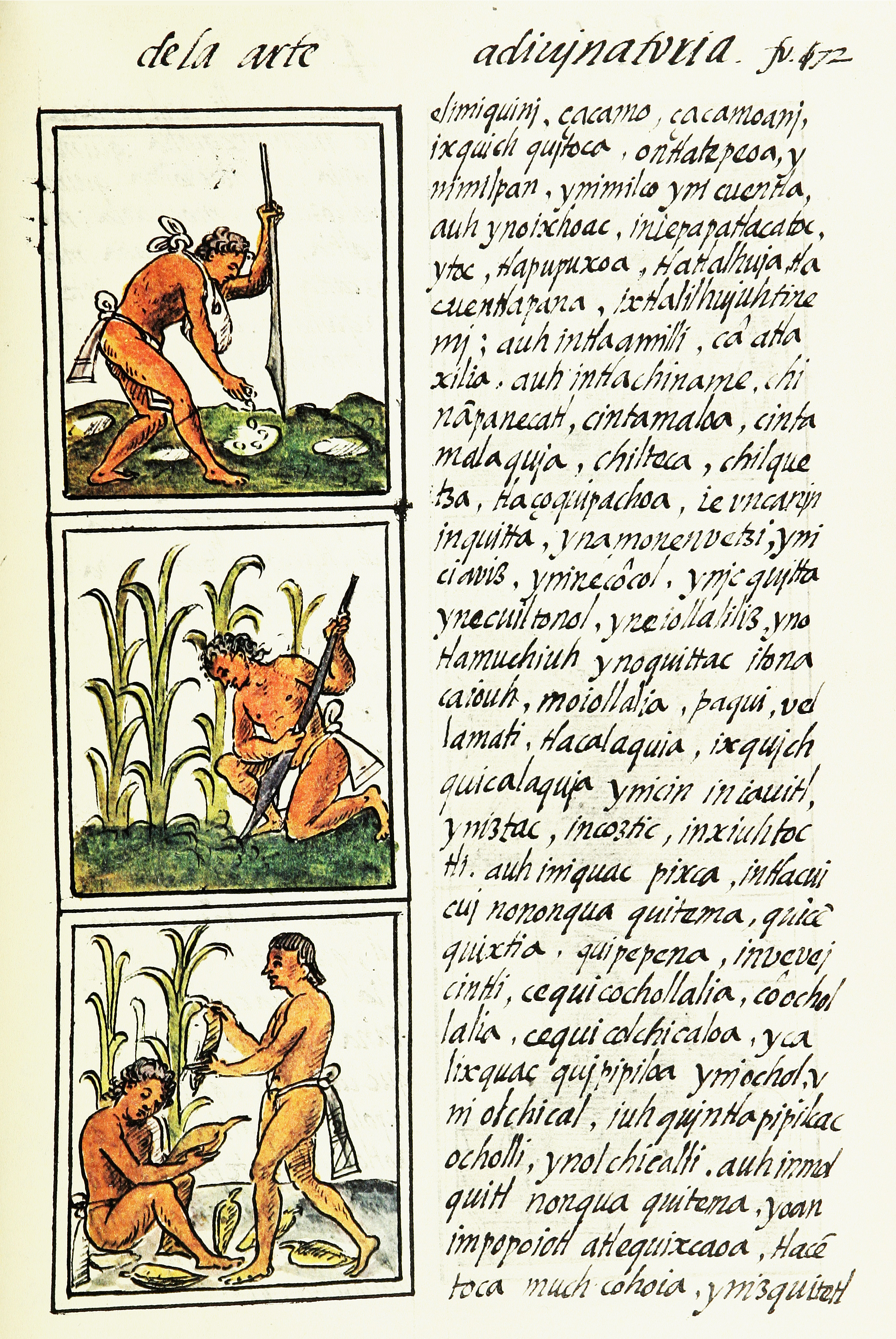

Seeding, tilling, and harvesting maize. Image taken from the 16th-century Florentine Codex. World Digital Library.

Enthusiasts for books concerned with ancient agricultural practices might have come across engravings of folk digging a pointed stick in the ground to seed the soil. More recent documentary footage of cultures where ancestral farming techniques are still alive shows the use of the said digging implement, notably in woodland, or rather forestland, cleared by the slash-and-burn method, in which native vegetation is cut down and burned off, the ashes serving as fertilizer for the new crops. Coa is one name given to the digging stick.

Farming has greatly changed since primaeval times both for us and remote cultures from afar some overoptimistic westerner decided to christen as “primitive”. The plough was quite a revolution, for it improved productivity; mechanical traction increased the area of arable land; synthetic fertilizers boosted productivity yet again; and modern glasshouses are the industrialized version of agricultural activity. Soil is no longer needed. An inert substrate is everything a plant wants to put down roots, and not even that for cultivation in hydroponics or aeroponics. Such technological complexity is argued by its advocates to be justifiable in order to ensure food supplies to an unstoppably booming population.

As shown in the last volume of the Ethnographic Atlas of the Basque Country, this one dedicated to agriculture, a significant number of family farms continue to exist in our territory. Although self-sufficient, they have incorporated various technological advances without turning their backs on the land. Taking an ethnographic approach, the cited work gathers knowledge and skills, mostly from our elders, in an attempt to make certain these are not lost.

Onion planting using a digging stick. Carranza (Bizkaia), 2013. Luis Manuel Peña. Labayru Fundazioa Photographic Archive.

Unexpected developments occur on occasion during data collection. Some years ago adverse conditions, including continuous rainfall, made us absolutely unable to adequately plough the land ready for farming. My mother needed to plant some onions, so she took advantage when the rain cleared up for a short while. I saw her sharpening a hazel stick and heading for the garden with it and a few bunches of onion plants. She dug into the soil with the sharpened stick and carefully placed a plant in the hole, its roots pointing down; then she pressed the soil around the stalk with her fingers and did the same with the whole lot. That was how the planting used to be done should poor weather make proper soil preparation difficult, she told me. For overgrown plants, she added, all you need is a thicker digging stick.

Luis Manuel Peña – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Language Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Reference for further information: Agriculture, part of the Ethnographic Atlas of the Basque Country collection.