Basque ethnography at a glance

Saint-Martin-de-Seignanx. Landes, c. 1900. Archives Départementales des Landes [Departmental Archives of the Landes].

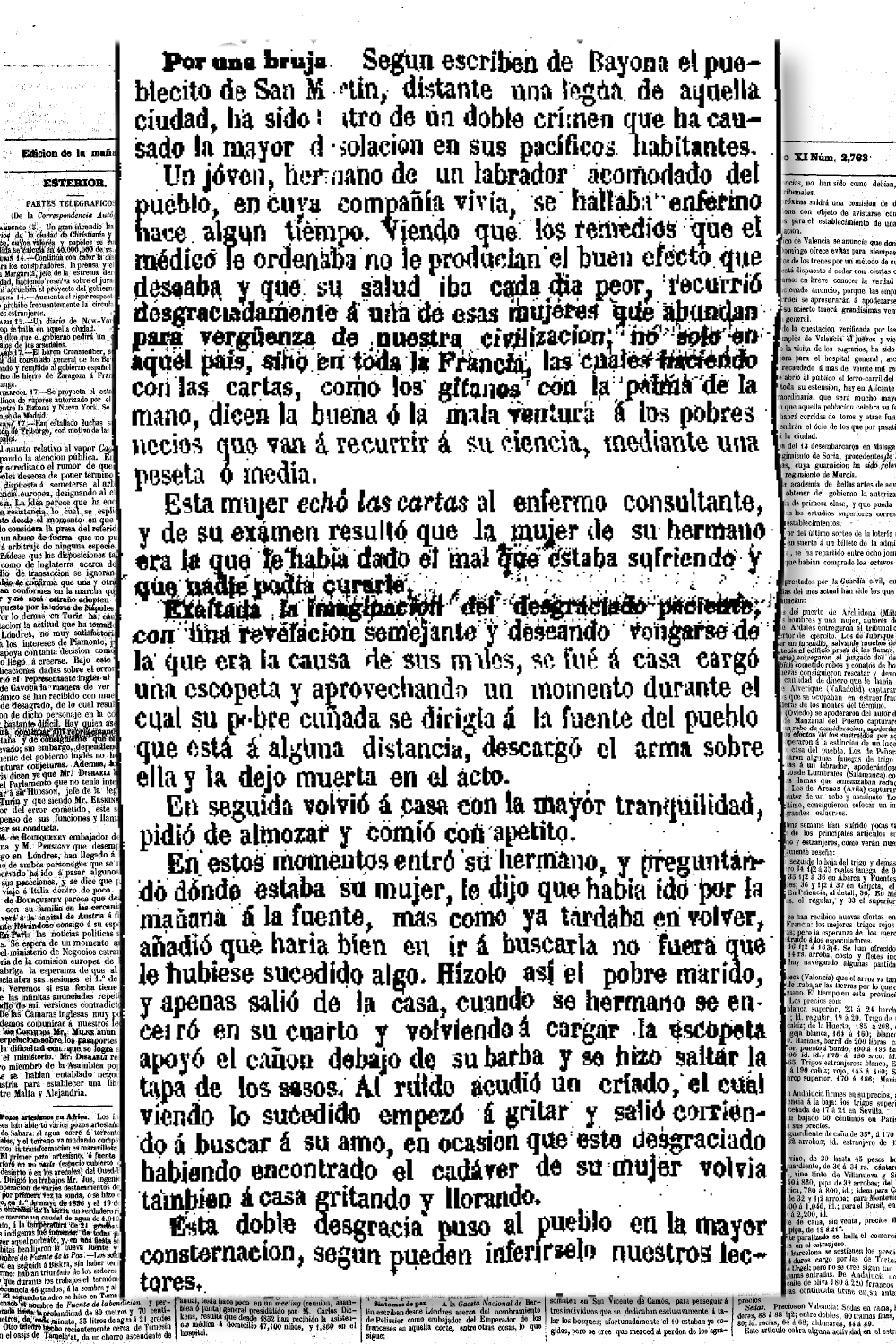

A terrifying report saw the light of day on the front page of the Madrid daily La España on 18 April 1858, published from 1848 to 1868 with the support of Pedro Egaña, an Álava native entrepreneur, and the Navarrese politician and writer Francisco Navarro Villoslada, leading representatives of ultraconservatism in 19th-century Spain:

By a witch

According to news from Bayonne, the village of Saint-Martin, a league distant from the mentioned city, has been the scene of a double crime which has caused deep distress among its peaceful inhabitants.

A young man, brother of a well-established local farmer whom he lived with, was ill for some time. As the remedies prescribed by the doctor would not have the expected beneficial effect, and troubled by iller health, he unfortunately resorted to one of those women who, to the shame of our civilization, abound not only in that country but in the whole of France, and who read cards as gypsies read palms, telling good or bad fortune to poor fools who turn to their science in exchange of one or half a peseta.

This woman read the cards to the consulting sick man, resulting from her examination that it was his brother’s wife who had done him wrong, and that nobody could cure him.

La España. Madrid, 1858. BNE [National Library of Spain] Newspaper Archives.

The imagination of the miserable patient having been fired by such a revelation, and motivated by a desire for revenging himself on her who caused the ills he suffered, he went home, loaded his shotgun, and taking advantage that his poor sister-in-law headed for the village source, located at a certain distance, shot her and left her for dead on the spot.

He then went back home with all tranquillity, asked to have lunch and ate relishingly.

At that moment his brother walked in, and upon asking where his wife was, he told him that she had been to the source in the morning, but as she had not yet returned, he added that he would do well to look for her, in case something had happened to her. The poor husband did as he was told, and hardly had he left the house when his brother locked himself in his room, reloaded his shotgun, placed its barrel under his chin, and blew his own brains out.

A servant turned up on hearing the noise, and seeing what had happened, began to scream and quickly left in search of his master, at which time, having found his wife’s body, the wretched man returned to the house screaming and crying in like manner.

This double disgrace aroused utter consternation among villagers, as inferred by our readers.

The events which disrupted life in the quiet village of Saint-Martin-de-Seignanx, very close indeed to the city and French Basque culture of Bayonne (although administratively Saint-Martin belongs now to the department of the Landes, and its identity can be considered part Basque, part Gascon), stand out within the ever so overwhelming anthology of rural dramas (past and present) to cast a shadow over many territories and many newspapers. The malevolent diagnosis by the card reader, the superstitious credit given by rustic provincials to fraudulent practices of divination, deficits in sound educational and cultural inputs, the traditional defencelessness of women against male-chauvinist aggressions, family rivalries and hidden tensions which often nest in small, isolated populations: all that contributed to the crime which took the life of that pitiable woman and subsequent suicide of her murderer.

This pattern of behaviour, with all types of variants, would sadly repeat on too many an occasion, unbearably similar cases being accounted for in two articles written by me some time ago and available on the net: “La sombra alargada de la Inquisición: brujería, violencia de género y noticias de prensa en la España de los siglos XIX y XX [The long shadow of the Inquisition: witchcraft, gender-based violence and press reports in 19th- and 20th-century Spain]”, Ra Ximhai 13, 2017; and “Vecinas viejas y brujas: violencia de género y comunitaria, entre tragedia y carnaval [Elderly neighbours and witches: gender-based and community violence, between tragedy and carnival]”, Inflexiones 2, 2018.

The tragedy unleashed in 1858 by a blind belief in the auguries formulated “by a witch” devoted to fortune telling with cards, staining with blood the village of Saint-Martin-de-Seignanx, on the cultural border of the Basque Country and the province of Gascony, along with crimes of a comparable nature repeated in many other geographies, are evidence of multiple regrettable issues; among them, the extent to which magic irrationalism and violence against women were, sad to say, active agents in the manifestation of numerous beliefs and behaviours of Basque and European rural folks during the 19th century (and beyond).

José Manuel Pedrosa – Professor at the University of Alcalá

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department –Labayru Fundazioa

Previous posts by José Manuel Pedrosa: Deadly clothing (I) and Deadly clothing (II).