Basque ethnography at a glance

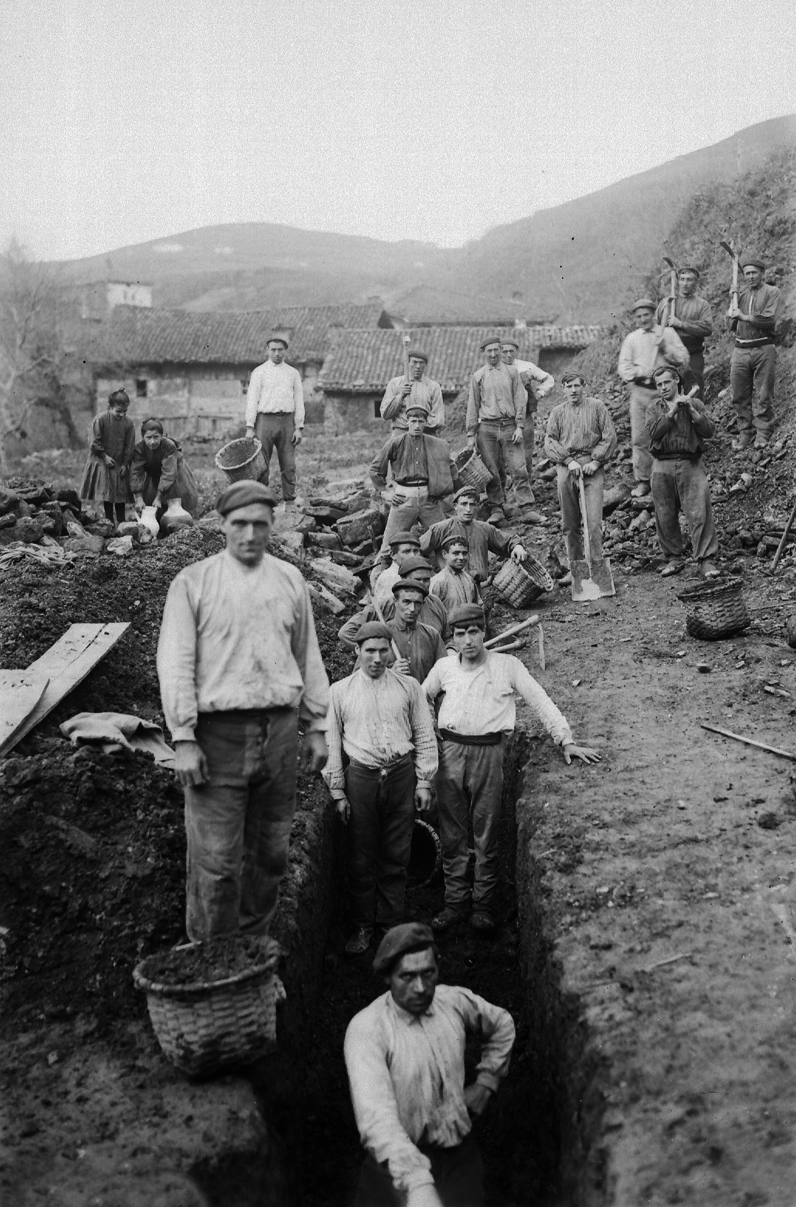

Old-time working bee. Zeanuri (Bizkaia). Felipe Manterola Collection. Labayru Fundazioa Photographic Archive.

In Basque-speaking locations the provision of services to the neighbourhood is known as auzolana. Communal work was more common in the past, partly because provincial and local councils have budgets to cover a wider range of needs and wants for all now than before. Such mandatory works for the community to which every household still contributes in some localities in Álava are there called veredas.

In former times neighbours gathered for mutually accomplishing major jobs they could not achieve on their own. Significant among them were road repair (bide-konpontzea) and the construction of local access roads running from farm to farm and the nearest urban centre. Households contributed their fair share of labour and also money to purchase materials, each in proportion to its economic capacity.

After construction, the roads needed to be maintained. Working bees were held regularly to repair potholes and clean roadsides (bide-hegalak garbitu). Likewise, when paths and tracks became impassable due to heavy snow, neighbours organized to help clear them.

Spading in Zeanuri (Bizkaia). Felipe Manterola Collection. Labayru Fundazioa Photographic Archive.

At that time when rural families lived with no running water, trenches were dug, pipes laid and much else, all by communal work parties, to bring water (ura ekartea) to their homes.

The neighbourhood hermitage was a meeting place for locals. There they gathered together for religious celebrations, the praying of the rosary, brotherhood meetings, and other matters related to the community. Repair to its roof and maintenance were carried out under the traditional system of communal work.

Many of our farms in Urdaibai encompass grasslands (bedar-lekuak) in the lowlands. At spring tides (ur-biziak) farmers carefully protected those areas along the watercourse with edge-of-field buffers (motak) using shovels (saka-palak) to dig and pile up chunks of turf (zohiak) for preventing saltwater intrusion and avoiding damage to meadows.

Besides a genuine concern for the common good, voluntary assistance among members of the community was the order of the day, more notably services and contributions in support of fellow neighbours in need (lorrak), which shall be dealt with in a future post. Typically, households promptly assisted one another with tasks which entailed a great deal of manual labour. At wheat-threshing (gari-jotea) bees, for instance, neighbours pitched in to thresh the wheat, which used to be done by hand before threshing machines were introduced, and were rewarded with dinner by the host family. Similarly, haymaking was another task shared by men and women alike, and all the more so ahead of impending storm. The same went for the slaughtering of the pig and other bees of various kinds. In some localities in Navarre this practice is known as tornapión and refers specifically to helping and receiving help from neighbours with seasonal farming commitments such as crop harvests, working of the land with spades in the old days, threshing of the grain, and grape harvest.

Care and assistance for neighbours experiencing the loss of a family member or close friend merits particular attention.

Segundo Oar-Arteta – Etniker Bizkaia – Etniker Euskalerria Groups

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa