Basque ethnography at a glance

School portrait. La Calera del Prado (Valley of Carranza), 1966. Courtesy of Miguel Sabino Díaz.

As a child, I have known elderly folks who could not read or write, though not many, to be honest. When asked to sign a document, they would affix their index fingerprint. Some had attended school for at least enough time to learn the four basic arithmetic operations and write their name, others not as long. Being able to write one’s name had its importance, and a beautiful penmanship with a flourish made it all the more admirable. In the course of my ethnographic researches, I sometimes come across old paper documents passed down from generations before me and see shaky, dubious handwritten signatures with nothing but a simple line under the name. The huge effort made by the signatories may well be perceived.

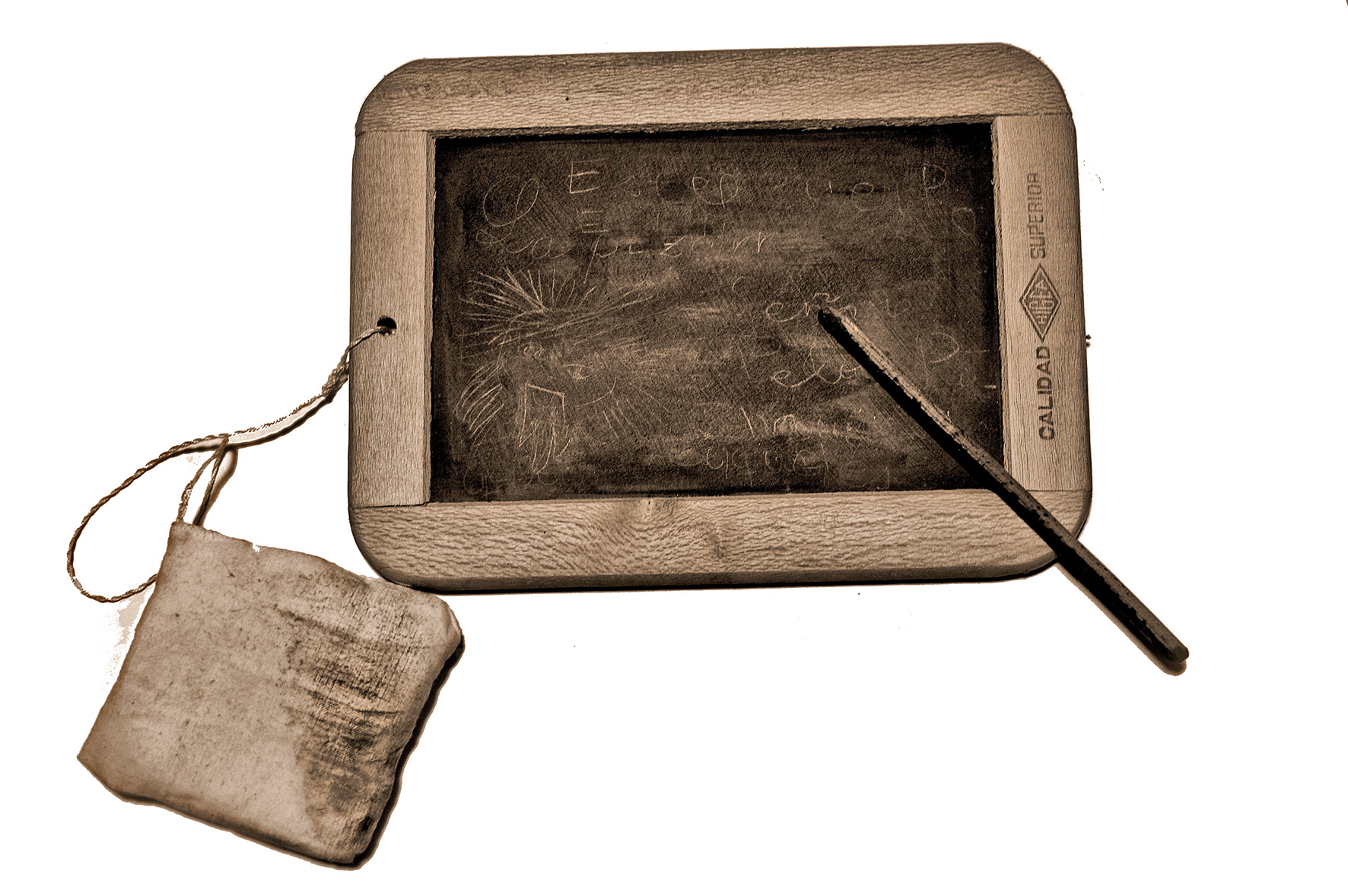

My grandparents and their generation used slate and slate pencils at school, and dip pens to write on paper. The same applies to my parents and their generation. In my first and rudimentary school, we had desks with inkwell holes. We did not come to use dip pens but were familiar with fountain pens. In point of fact, fountain pens and ballpoint pens were traditional first communion gifts. Pens and pencils were common classroom resources in my day. Ballpoints were of so poor quality the cold of the winter caused the ink to dry up and clog the tip, in which case we scribbled energetically on a rough piece of paper in an attempt to revive the pen from collapse and restore it to working order again, or rubbed it between the hands with the same prehistoric gesture as for making fire with a stick, or breathed repeteadly on the tip hoping to free up the ball and get it rolling smoothly again. We became experts in transplants, forever dismantling faulty nibs on ball pens and fitting ink tubes with some old, worn-out tip that would still work. As often as not, the ink flow stopped, so you had to put heart and soul into blowing hard in the clear end of the tube until the pen started pumping again, which left you really red in the face.

Slate with pencil and wiping cloth. Miguel Sabino Díaz.

Pencils were not much better. The graphite in them was prone to easily breaking, and sharpeners were scarce and so blunt the fragile leads cracked time and again. Be that as it might, we usually used a knife or a blade to sharpen them. We also did not always have a rubber to rub out what was written, then used instead breadcrumbs knead into a dough with the fingers. Felt-tip pens followed colouring pencils over time. They dried out fast, but we could not afford to replace them with new ones, so made them live longer by alcohol transfusions, which we performed with extreme care because of the high risk of colour haemorrhages.

Years have elapsed and the means to write, and also sign, have evolved significantly. Pens and pencils are of excellent quality today (except for promotional stationery), and the use of so-called propelling pencils or leadholders is widespread. Felt-tip pens with extra fine and firm writing tips might have been an unprecedented achievement; however, the development of digital technologies has reached its highest level of sophistication in the form of touchscreens. For banking formalities and acceptance of goods delivered, we are now requested to apply our signature on a screen with a signing device similar to graphite for drawing, which is devilishly difficult to do and results in hardly illegible handwriting that reminds me of the aforementioned shaky pen-and-ink signatures of my ancestors.

Nevertheless, I experienced even greater refinement the other day when, having had the car checked, I was asked to sign on a touchscreen not with a signing pen but my index fingertip. After incredible advances, I thought, we have ended up singing with the tip of the finger, just as yesteryear folks who had never had the chance to learn to write did.

Luis Manuel Peña – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Good site you have here… It’s difficult to find quality writing like yours these days. I truly appreciate individuals like you!

Take care!!

Thanks ever so much for your nice comment!