Basque ethnography at a glance

Regarding the term kuarta tenpora, most commonly used among us to designate these four sets of three days, and contrary to what it might seem, it does not allude to the fact that such celebrations took place four times a year, but comes from Latin feria quarta. In origin, that is to say, in Roman times, and from a religious point of view, ember days —the mentioned kuarta tenporak in Basque— were quarterly periods prescribed by the Church for fasting and prayer. As for the name feria quarta, it provided a means to designate a certain day of the week in Latin: starting from Sunday, Monday would be the feria secunda; Tuesday the feria tertia, feria quarta thus being the denomination of Wednesday received by the Church in Latin. On Epiphany, 6 January, from the pulpit of the parish church, the proclamation of the most important religious feasts of the liturgical year would be read. And quatuor tempora days were also announced, specifying the initial day, Wednesday, beginning with the opening formula Feria quarta tempora erit…, and subsequently giving the dates for each fasting and prayer day.

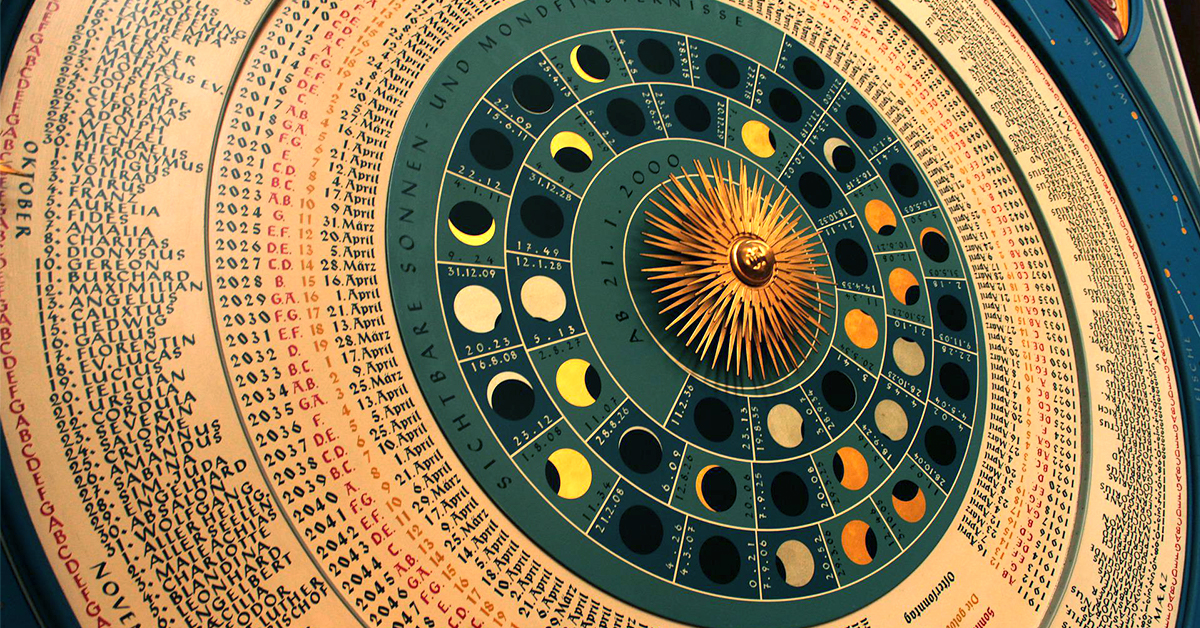

That said, seasonal ember days have their deepest roots in pre-Christian times. Because of their origin and meaning, ember days are closely related to the conception of time —chronological and historical, not meteorological— in traditional rural societies, which could be summarized in two types: linear or cyclical. A modern, linear conception of historical time stands out, in general, as the most widely adopted in present-day societies. The cyclical view would nonetheless prevail in ancient cultures, having its foundation in the observation of the different cycles which normally exist in nature: the seasons, the changing positions of stars, celestial bodies or planets, and so on.

Ember days being prior to Christianity, from this cyclical conception of time, periods of systematic exploration of nature were established at the beginning of each cycle for folks to anticipate their agricultural activity during the following four months, and I would even dare to say, to ask nature to be benevolent during that period. Well aware of the deep-rootedness of embers days, the Catholic Church decided to turn them into times of penance, addressed though not to mother nature, ama-lurra, in this case, but to the supreme being called God, and keeping the same dates of the year as before.

Abel Ariznabarreta – Historian

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa