Basque ethnography at a glance

As we know, thousands of Basques emigrated to the west coast of the United States at the end of the 19th century and during much of the 20th century. Men, women, young people, entire families… followed in the footsteps of relatives and friends who were already established there. Encouraged to join their predecessors, they embarked on a journey in search of a more prosperous future full of hope. Among the Basques who arrived and settled in North America, the largest group would be made up of men who worked as shepherds.

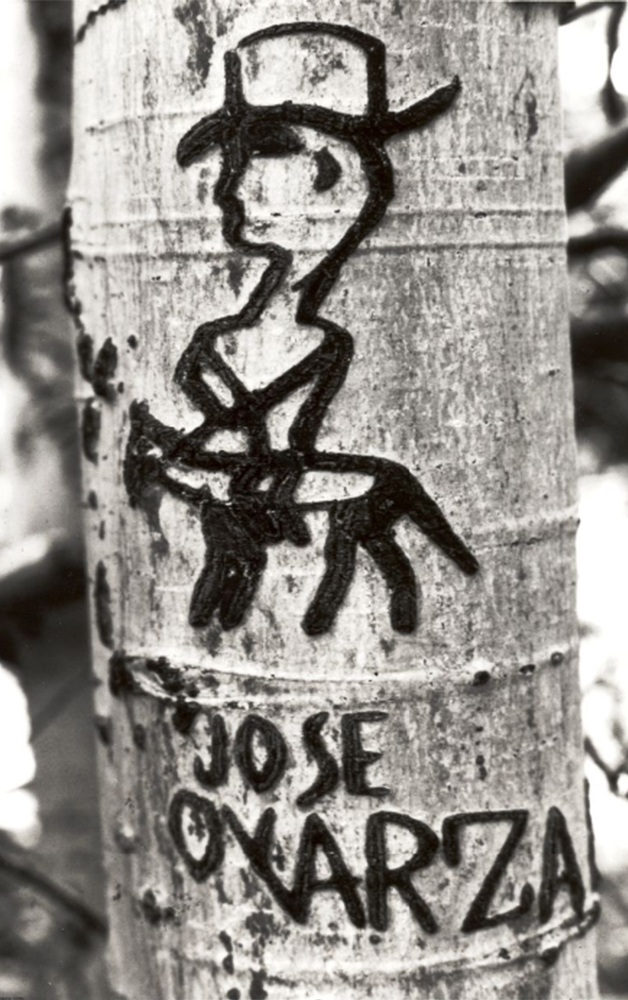

Far from their families and villages of origin, the Basque shepherds travelled long distances for their sheep to graze peacefully in the vast meadows. Days passed very slowly, and while they kept watch to ensure that the flock was properly fed, they would carve their names, thoughts and fantasies into the bark of the trees. Most of them wrote their name and the date, and the more daring engraved texts or drawings on other subjects, such as their political or religious beliefs, the Basque homeland, or their deep-felt desire for a woman.

Although one might think that the herders performed this artistic activity no more than for their own entertainment, their engravings also served the practical purpose of conveying to their fellow countrymen helpful information about the best locations for grazing. Should a shepherd find inscriptions of other shepherds who were there before him, and long enough to materialize their impressions on the various poplars far and near, then he knew that he was in the right place, surrounded by the finest of pastures for his flock. Moreover, coming across such engravings comforted him and made him feel part of their same culture or heritage, encouraging him to add his own to the existing ones.

Arborglyph: Man on a horse. Photo credit: Joxe Mallea-Olaetxe. Source: Jon Bilbao Basque Library. University of Nevada-Reno Libraries.

A simple knife or razor was all that they needed to capture their thoughts on the trunk of a tree. A small, barely visible incision was made in the chosen trunk to shape the words or images to be engraved. The groove took up to two or three years to be appreciated, so the author would simply and purely let nature do its work. The shepherd carved ‘blindfolded’, as it were, not knowing what would become of what he was depicting on the skin of the cherished poplar, for the tree itself would take over and continue what he started, once the incision was finished. As the wound healed, the marks would gradually turn darker and darker, and stand out more and more on the light wood of the poplar. A skilled engraver knew how to choose the right tree and the right tool to make a very fine incision at just the right depth for the perfect scar to emerge. The beauty of many carvings made by Basque shepherds is indeed noteworthy, considering that they came from the rural world and lacked graphic or artistic training.

These vital, and at the same time, popular forms of expression respond to the need of those men to express their feelings and leave their mark on the only possible medium available to them there and then: nature. They are graphic and written manifestations of humble people, with profound and sincere personal messages, concentrated in the forests of the American West and which reflect a whole reality of the migratory past of the Basques.

Many of them still remain there where they were created, unaltered for now, but unfortunately cannot be preserved for the future, their permanence being a hard fight against the clock. Engraved in living wood, their life is linked to that of the tree which supports them. The very course of nature is causing their disappearance, perhaps, and symbolically, bearing significant testimony to the end of the presence of the Basque shepherds on the prairies of the Western United States.

Zuriñe Goitia – Anthropologist

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa