Basque ethnography at a glance

The term “romeria” (erromeriak) or pilgrimage originally referred to the pilgrims’ journeys to Rome or other centres of Christianity. By extension, it has come to mean, in popular tradition, the festivities where people gather in meadows or on hillocks around certain chapels or shrines. It also encompasses the influx of pilgrims, religious services or festive events involving the pilgrims and the general public, at those sacred or devout places. Pilgrimages are organised in periods of good weather and usually take place in spring and at the end of autumn.

On the other hand, Lent was not a suitable time for organising such pilgrim celebrations, as it was a time of spiritual recollection, of public entertainment (weddings, dances, demonstrations of joy, games and gambling, etc.) being suspended and of austere fasting or vigils. The latter were only less severe in certain exceptions (in cases of illness, pregnancy, work, etc.), the issuing of dispensations in return for a consideration, or general or individual Lent bulls.

The feast day of St. Joseph (19 March) is at that time of year, on the cusp of the start of spring and under the spiritual recollection of Lent. It marked the first pilgrimage of the year in Bizkaia. In particular, in the old Deusto anteiglesia or parish (commemorated since the early 20th century) and has achieved unprecedented fame (and it has, nowadays, even overshadowed the St. Peter’s patron saint festivities). In the run-up to that date, the garments to be worn on that day were prepared and the keen pilgrimage-goers used to say: “It’s St. Joseph’s day and we are going to get out the white espadrilles” or “The first white espadrilles of the year!”. They tried not to damage that footwear, looked after it and whitened it with chalk.

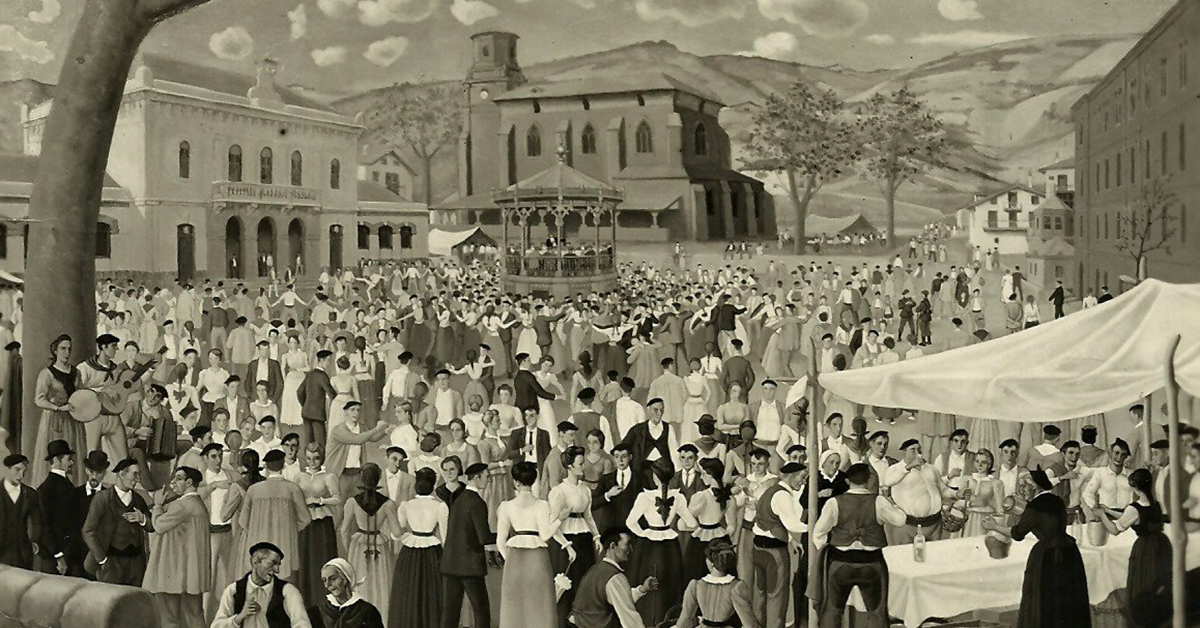

At nightfall on the evening before, the municipal band would go to the local homes of the people called “José” [Joseph] and dedicated a paso doble to them. The St. Joseph pilgrimage was very busy and attracted crowds from different towns (Erandio, Sondika, Abando, Bilbao, Derio, Basauri, Getxo, Arratia, etc.). The pilgrims would make their way on foot to San Pedro square where, after High Mass and the dancing of the traditional Aurresku, the crowd (in groups of friends or relatives) would visit the “txosnas” stands and tents selling food (run by “La Ceñuda o Sañuda”, “La Novilla”, etc.) and the temporary premises of the “txakolin” (“La Parra”, “Los Odria”, “Ortuondo”, “Matxintxu”, etc.) to typically eat roast lamb with salad. This was the traditional dish of that day, as the bishopric bull or special licences included the local residents and the pilgrims there.

In the evening, the custom was for the pilgrims’ dance to be held in the local square or public spaces. The music would be provided by the band alternating with the municipal drummer or txistulari. Meanwhile, different travelling musicians (who were not entitled to perform in the square: playing tambourines, accordions, guitars, violins and the dulzaina (Spanish double reed instrument), etc.) and that marked the start of their annual pilgrim’s journey. They would set up on a raised height, where their groups of followers would gather, and perform their repertoires (dances “in hold”: paso dobles, chotis, tangos, habaneras…; and “individual”: jota and “purrusalda”). The young people were charged a set amount 10 cents (perra gorda as the ten-cent coin was called) per dance and 1 peseta for the whole afternoon. The public dance and the St. Joseph pilgrimage would end at nightfall to the sounds of the band (with jota and/or paso doble). To then be performed again with less splendour in its repetition or octave.

Josu Larrinaga Zugadi – Sociologist