Basque ethnography at a glance

Luis Manuel Peña. Labayru Fundazioa Photographic Archive.

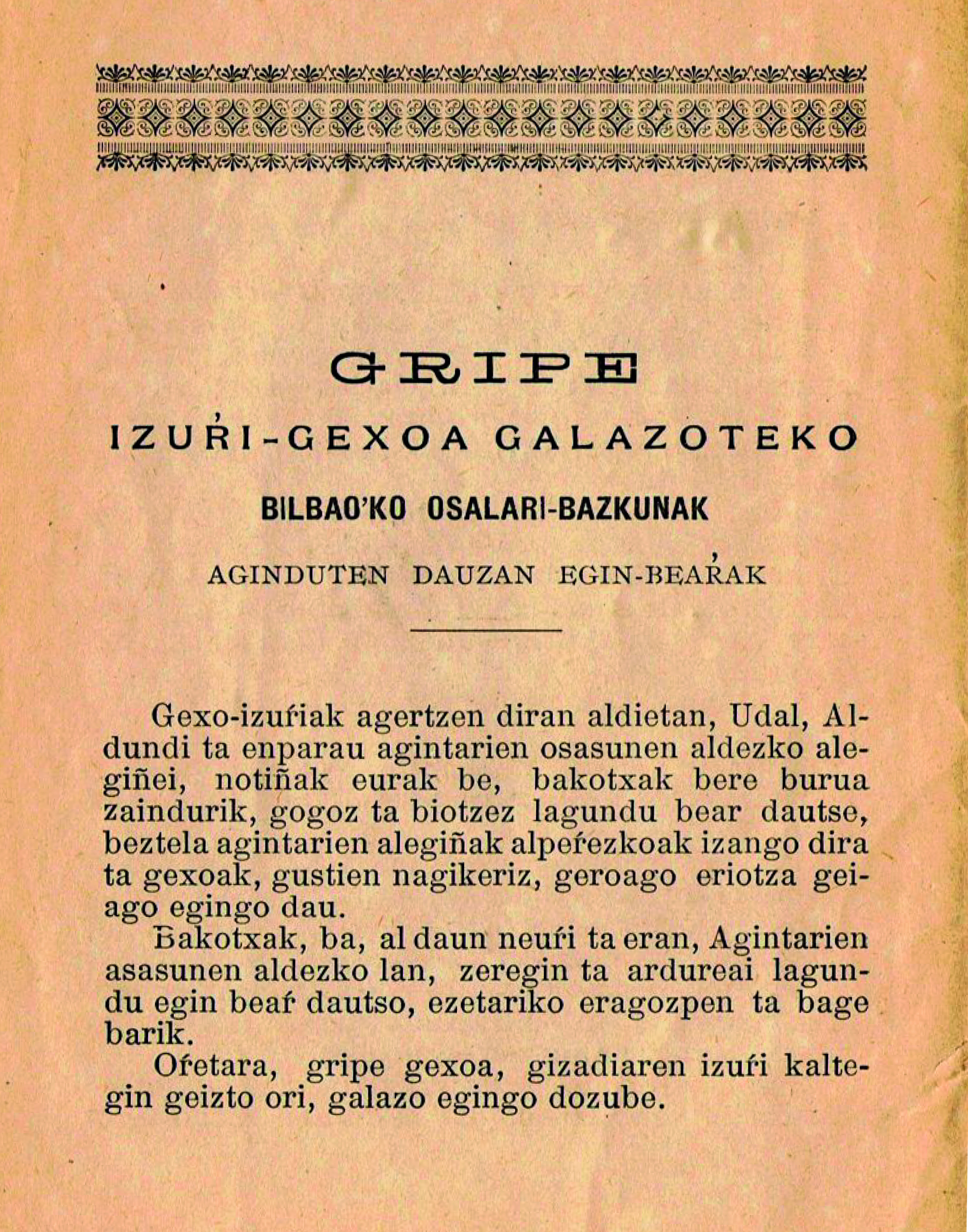

Contagious diseases are as much cause for concern now as they were before. Broadly known as gaitz kutsakorrak, in Basque, or kutsuzko gaitzak, they are referred to as gexo iraskorrak, —gaixo eranskorrak, as we would write it today— in the manual of recommendations distributed by the health authorities of the city of Bilbao in 1918 under the heading Gripe izurri-gexoa galazoteko Bilbaoko Osalari-Bazkunak aginduten dauzan egin-beharrak, which we translate as Prophylactic measures recommended by the Academy of Medical Sciences of Bilbao for combating the influenza epidemic. Basque equivalents for ‘infecting’ or ‘being infected’ are kutsatu —perhaps the most widely spread— erantsi, nahastau, pegau, itsatsi or even inkau.

When a contagious disease turns into an epidemic in a specific location or geographic area, its impact on social life is extraordinary. Let alone if it spreads sustainably in communities and across borders before finally being declared a global pandemic. Particularly alive in our collective memory is the pandemic influenza of 1918, unwisely called ‘Spanish flu’. It is estimated that more than half of the world’s population were infected, causing significant mortality also in the Basque Country. In actual fact, it became the deadliest health crisis of the 20th century.

Contrary to the novel coronavirus, the flu pandemic of 1918 showed a preference for young adults. Entire families became infected in some of the most severely punished localities, their neighbours having to take care of them and their livestock. The pandemic attacked Orozko and Zeanuri, in Bizkaia, particularly hard, wreaking havoc —etxe batzuk hutsitu egin ziran ‘entire households died’, as it was said—.

As elderly folks would recall, the dead were wrapped up in sheets because of lack of coffins in some locations. Holy water basins at churches were emptied out, and the tolling of church bells for the dead ceased not to alarm the ill. In the belief it could avoid contagion, all who came into contact with the infected, among them the sacristan and the priest who administered the last sacraments, carried bulbs of garlic in their pockets and a clove in their mouth, it was said.

Squatting couple, also known as The family by Egon Schiele, 1918. Belvedere Museum of Vienna.

To stem a pandemic, contagion must be averted by every means. Indeed, forceful implementation of a cordon sanitaire, inevitably including isolation, was and continues to be the general and urgent remedy for contagious diseases to stop from spreading. The affected were, in some cases, confined to lazarettos or hospitals away from population centres; in others, they and their families were placed in quarantine in their own homes.

As stated in the above-mentioned set of instructions, a number of precautions are necessary to prevent contagion in times of pandemic: wash one’s hands thoroughly and frequently, cover one’s nose with a tissue when coughing, ventilate homes properly… It likewise instructs city residents that they should use lime to whitewash walls and evaporate an aqueous solution of formaldehyde or disinfectant to sanitize rooms.

The arrival of the summer curbed, on that occasion, the spread of influenza virus in our country, but in the autumn, with the reversal of the weather, the flu reappeared and hit with more virulence than during the milder first wave, reaching highest mortality in October 1918. Let us hope history does not repeat itself this time.

Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa

References for further information: of indisputable value and interest is the manual Gripe izurri-gexoa galazoteko Bilboko Osalari-Bazkunak aginduten dauzan egin-beharrak.Instrucciones profilácticas aconsejadas por la Academia de Ciencias Médicas de Bilbao para combatir la epidemia gripal[Prophylactic measures recommended by the Academy of Medical Sciences of Bilbao for combating the influenza epidemic]. Bilbao, 1918; also the research work by Anton Erkoreka La pandemia de gripe española en el País Vasco (1918-1919) [The Spanish influenza pandemic in the Basque Country (1918-1919)]. Bilbao, 2006; and Popular Medicine, part of the Ethnographic Atlas of the Basque Country collection.

Note: Both Egon Schiele and his pregnant wife succumbed to the influenza pandemic of 1918.