Basque ethnography at a glance

Until well into the second half of the last century, children entered formal education at six or seven years of age. Compulsory schooling was of short duration, usually up to the age of twelve, or fourteen at most, depending on the demand for hand labour in the respective family’s household. In addition to the standard schooling period being not long enough for the appropriate instruction of boys and girls, there was also a high level of school absenteeism, especially in rural areas, due to the urgency of farm chores and the inclement weather. For a good number of scholars, heavy precipitations and low temperatures would sure make their long daily journeys on foot from the farmhouse to the school exceedingly difficult.

Even in localities where Basque was by far most commonly used, both at home and in the street, Spanish would officially be the language spoken and taught at boys’ and girls’ schools. The aim of education was basically limited to pupils learning to read, write, carry out simple mathematical operations and acquire sound knowledge of Christian doctrine. Girls were also taught sewing skills.

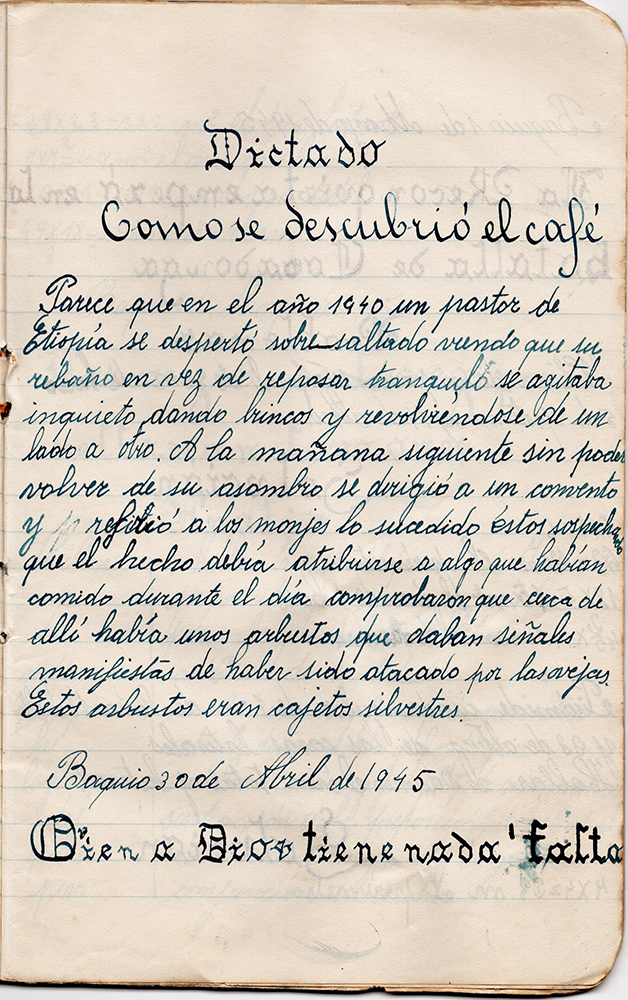

My grandmother’s old school notebook came into my hands only a few months ago. Its pages are ruled and written with a fountain pen. Along with a few interspersed religious phrases, the notebook contains dictations, essays, grammar exercises, and mathematical problems with their solutions. The subject matter of the exercises is almost invariably rural (crops, livestock, peasant buying and selling…). And a recurrent feature throughout the notepad particularly struck me: namely, the quality of the handwriting and the beautiful calligraphy.

Once upon a time, it was not just a matter of knowing how to write, but how to write properly, calligraphy being therefore of great importance at school. The learning of writing technique was achieved by imitating the teacher’s handwriting on the blackboard, repeating the different calligraphic models in special notebooks, or copying the various types of calligraphy from school manuscripts.

The invention of the ballpoint pen revolutionized the process of learning calligraphic writing technique. With the advent of typewriters, typing replaced calligraphy, which in turn would be later replaced by computer keyboards. The need to write by hand diminished dramatically over time, and curiously enough, our very scarce manuscripts increasingly resemble computer printing nowadays, characterized by simple and separately written letters.

In cursive, joined handwriting, this is how my amama’s school notebook ends: It’s the last day of school, a very sad day, because I am leaving school for good and shall never play again, nor read nor do what I used to do before. School times have been happy times! Having finished school, she devoted herself to the family farm, working out in the fields and tendering to the livestock, doing household chores and caring for the elderly members of the family. It must have been a big change in her life, and that is for sure why she would treasure her school notebook and held on to it for the rest of her life, as well as everything she learned from it, particularly the art of calligraphy.

Zuriñe Goitia – Anthropologist

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa