Basque ethnography at a glance

Several weeks ago we concerned ourselves with the life cycle of us humans in traditional society [See The cycle of life]; on this occasion we shall attempt to outline the transmission wheel of the chronological passing of the years while distinguishing workdays from holidays.

As we pointed out in that previous post, we are for sure influenced by geographical structure, social context and historical time, all personal or collective activity within the cycle of everyday life (be it a working or a non-working day) being marked by a set of rituals meant to promote its success. Traditionally conceived as cyclical processes repeated endlessly, they are susceptible to a number of unchanging regularities or constants which have been observed and transmitted by generations.

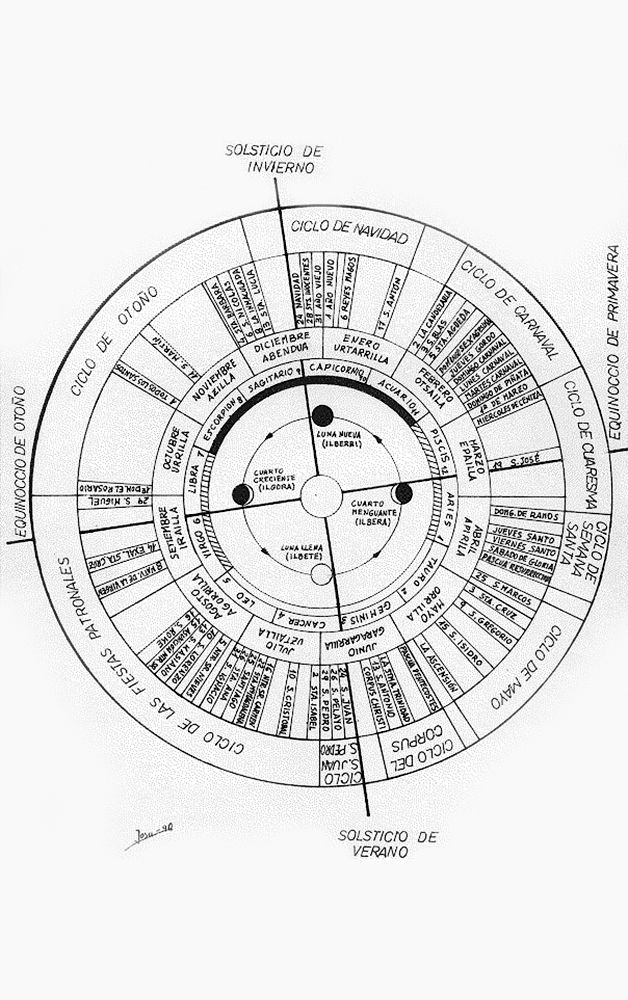

The festive cycle, in its constant concatenation of seasons, according to the position of the main stars (Sun and Moon) or zodiacs, and the sequencing of the different cycles within the cycle or constitutive festive celebrations are directly connected with the occupations or specific productive activities of a given community.

Let us begin our brief analysis with the autumn equinox, which marks the harvest of agricultural crops, the return of livestock from mountain pastures, and the end of the prime fishing season. Starting round about St Michael’s Day and until early December folks gather and prepare for the rigours of the coming winter.

Inclement weather strikes as we head into the dark and cold time of the winter solstice. Christmas stands out at this stage of the year, featuring unique solstice celebrations of pagan and Christian syncretism. A feast cycle of variable date (determined by the full moon of Easter) follows, bound by the shared need to nurture social interactions for the protection of the community, exchanges of food species for glad tidings, and social cohesion of peoples: carnival and other rituals observed after the sowing season are indeed a much awaited spell of common relief.

That extraordinary outburst of revelry would be countered by the restrictions of Lent: marriages and entertainment were limited, fasting and abstinence prescribed. The awakening of Nature in March and the various rituals which accompany the spring equinox demand for care and attention to fields, fisheries and herds moving to summer pastures. The variability of Easter invariably brings about the Passion of Christ year in, year out, along with a series of rituals for the preservation of plant, animal and human life. And a cluster of celebrations around the feast of Corpus Christi anticipate the impending arrival of the summer solstice.

The symbolic rituals (purifying water and fire) of St John’s Eve and Day prove decisive for successful fishing, farming and livestock grazing during the summer and beyond. These are times of abundance, and festivals are held in honour of our patron saints, allowing ourselves plenty of eating and drinking opportunities. And to be safe rather than sorry, surpluses are preserved for prospective shortage periods.

That is to say, the above-mentioned vital annual processes and particularly the regulation of communal festivities within the bounds of traditional culture define the order and periodicity of all economic or subsistence, social, spiritual and cultural activities for an entire community.

Josu Larrinaga Zugadi – Sociologist

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa

The text is also accessible in Basque and Spanish, either by changing the language of the website or by clicking on the following links: Jai-zikloa betiereko itzuleran and El ciclo festivo en el eterno retorno.