Basque ethnography at a glance

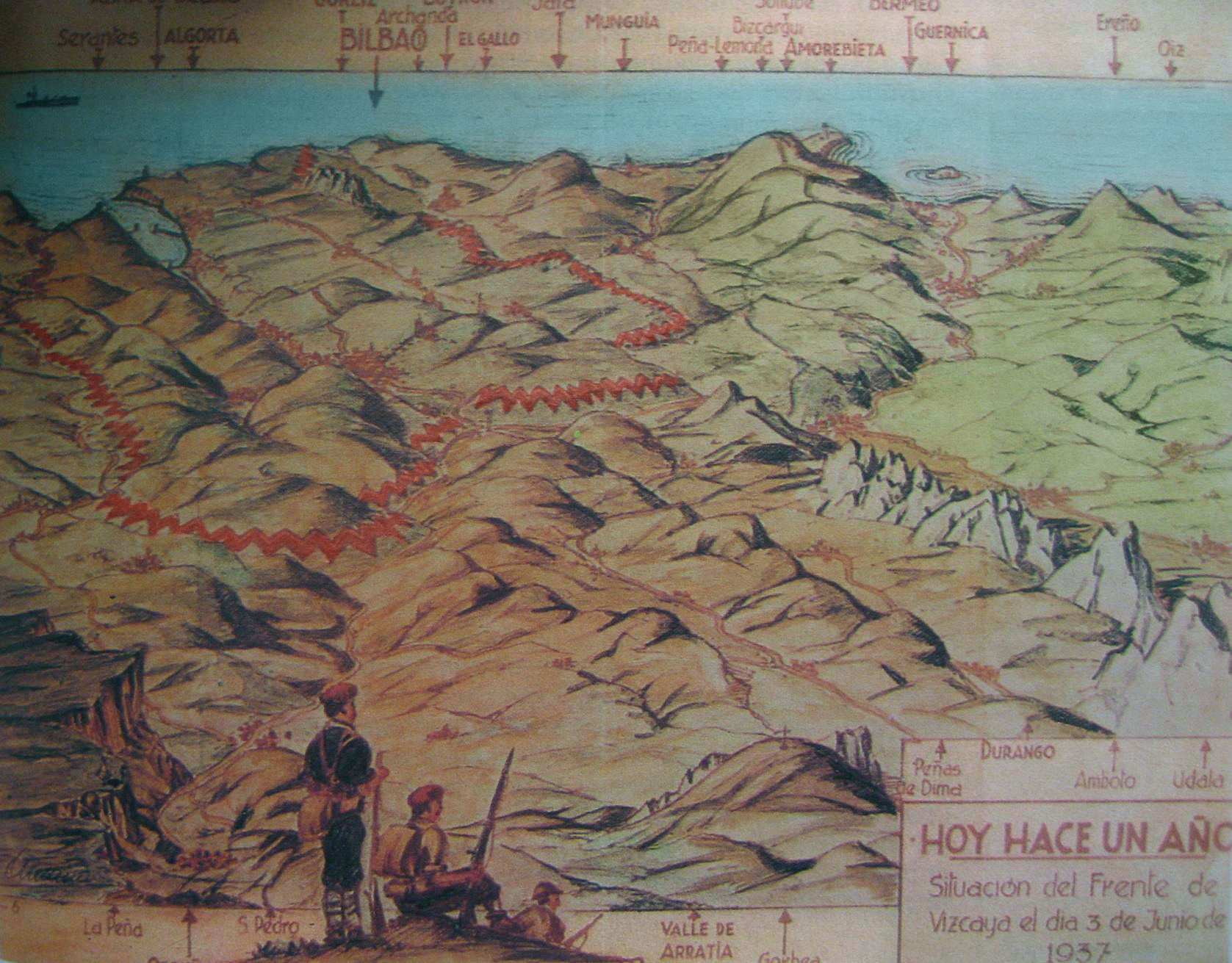

Francoist propaganda illustration of the Iron Ring.

In the midst of the Civil War, in early October 1936, after the fall of Gipuzkoa into the hands of the rebel troops and the consolidation of the Basque resistance, the Bizkaia Defence Board acknowledged the need to provide Bilbao and its immediate surroundings with defensive works as protection in the event a new attack by Franco’s army managed to break the established front line. Days later the recently-formed Basque Government presented the draft. José Antonio Agirre, then defence counsellor, along with the head of the Basque Government, commissioned Engineering Commander Alberto Montaud to undertake the construction of what was called Bilbao’s Defensive Ring: a vast fortification consisting of a ring of trenches, machine-gun positions, strongpoints and secret bunkers. The Ring was divided into five sectors running along the route Zierbena – Sodupe – Miraballes – Usansolo – Larrabetzu – Barrika, the city of Bilbao, the Lamiako and Sondika aerodromes, the harbour with battery emplacements at Punta Galea and Punta Lucero, the Zollo reservoir, and the power station at Burtzeña lying within its borders. It covered overall a perimeter of 80 km over the mountains around Bilbao, defended by 45 000 gudaris and militia members of the Army of the Basque Country.

Machine-gun nest at breakthrough point on Gaztelumendi (Larrabetzu). Indalecio Ojanguren. General Archive of Gipuzkoa.

The works were carried out by some 10 000 labourers and management. Montaud also relied on professional assistance from a couple of military officers, who professed loyalty to the Republic but supported the rebels. Captain Pablo Murga, for one, acted as an informant for an espionage network directed by the Austro-Hungarian consul, and was subsequently tried and executed. The other, Captain Alejandro Goicoechea, changed sides on 27 February 1937 and fully informed the enemy about the location and construction details of all defensive elements of the Ring. And so it was that pro-Franco troops learned enough about the infrastructures under construction: deep trenches with a bench for the firer and sandbags, open or concealed with pine logs; shielded machine-gun nests, built from stone masonry and with reinforced concrete shells; concrete sheds pierced by multiple embrasures for firing; shelters in tunnels and other underground cavities; lines of wire fencing supported by iron posts; fortified observation points; and other additional elements. Only 40 % of it had been finished by the time of his desertion, according to Goicoechea. More importantly, however, he supplied valuable information concerning the location of three unfortified sites where the Ring could be breached and broken. It was precisely at one of those sites, between Mounts Gaztelumendi (Larrabetzu) and Urrusti (Gamiz-Fika), the attack would be launched.

Unable to conquer Madrid, General Franco’s army attacked the North, specifically the Basque Country, on 31 March 1937. Despite the slow advance of his troops, they eventually reached the mentioned weak spots in the Ring. On 12 June 1937 Franco’s overwhelmingly superior forces, including 110 warplanes, 180 artillery pieces and 12 000 soldiers, penetrated the weakened Basque defences and breached the Ring. A week later, on 19 June, Bilbao was lost after a last stand in Artxanda. In the meantime Francoist propaganda coined the term ‘Iron Ring’ to give greater prominence to their conquest. Years later the engineer Goicoechea, for his part, achieved worldwide fame with the introduction of Talgo trains.

Aitor Miñambres Amezaga – Memorial Museum of the Iron Ring (Berango)

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa

Reference for further information: Aitor Miñambres. “El Cinturón de Hierro [The Iron Ring]” in Historia de Plentzia: La Guerra Civil en Plentzia y Uribe Kosta [History of Plentzia: The Civil War in Plentzia and Uribe Kosta]. Coordinated by Gonzalo Duo. Lankidetzan, no 63, 2017.