Basque ethnography at a glance

![Image taken from Bidegileak [Forerunners], 4.](https://www.labayru.eus/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/bidegileak-portada-bizentamogel-b.jpg)

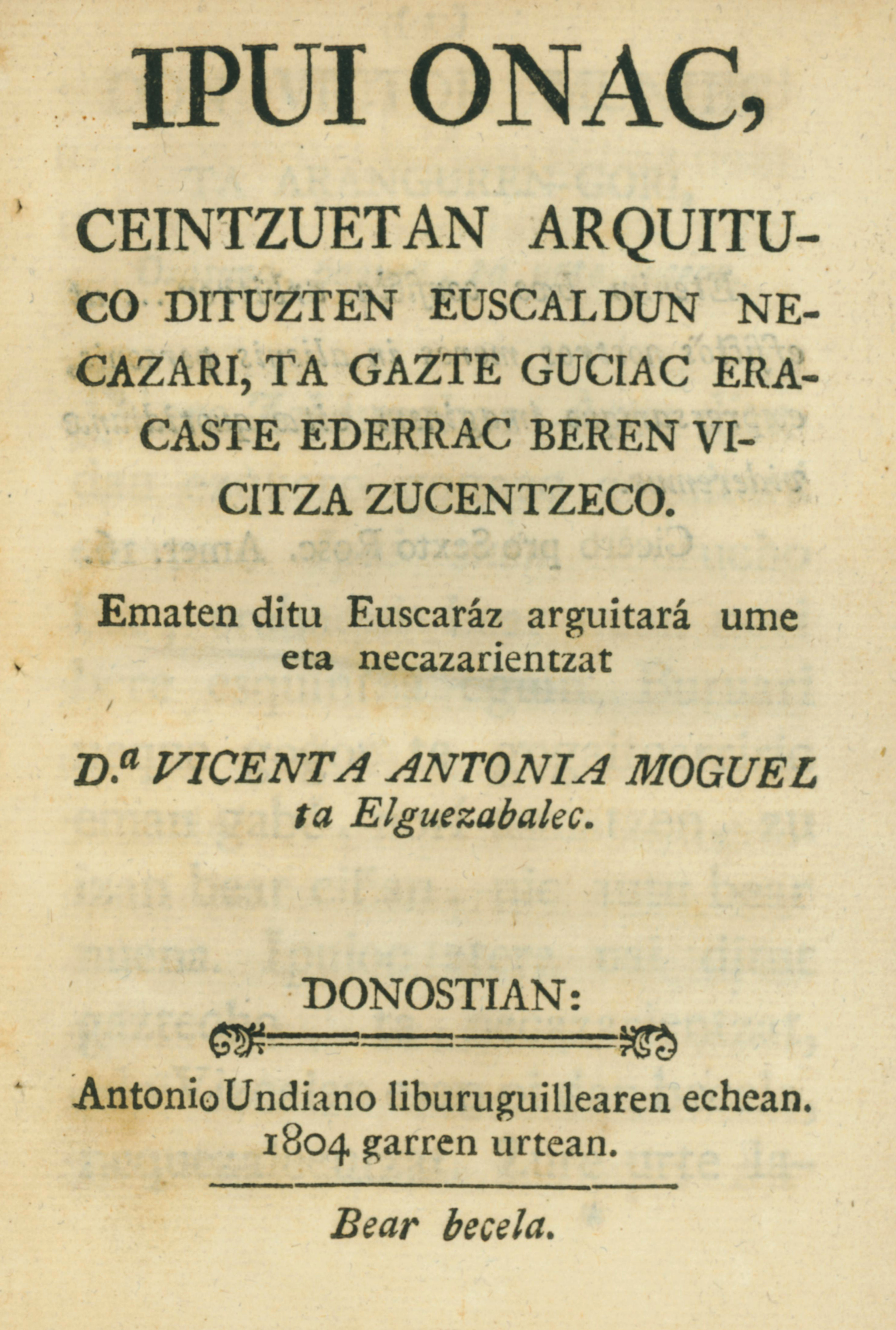

Bidegileak [Forerunners], 4. Euskal Biblioteka. Labayru Fundazioa.

Vicenta Antonia Moguel (1782–1854) is the first known woman to write in Basque. She was the youngest sister of Juan José Moguel (1781–1782), also a writer. A number of circumstances are essential for a person to become a writer, among others, writing skills, enjoyment of writing, creative talent, and intelligence. In the case of Vicenta Moguel, family circumstances, specifically her father’s early death, prompted her uncle, the famed writer Juan Antonio Moguel (1745–1805), to take care of the education of his niece and nephew.

Open minded and with an awakened mind, Vicenta learned from her uncle not only the rudiments of a traditional education, including how to read and write in Spanish and Latin, but also the use of the Basque language, both from Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa. She published her first book in 1804, the year her uncle Juan Antonio Moguel died, at 22 years of age. Titled Ipui onac [Valuable fables], the booklet includes 50 Latin prose fables by Aesop rendered into Gipuzkoa Basque. As she herself argues in the prologue, the young writer is aware that for a young girl of the period to write and publish a collection of fables would be frowned upon. As she puts it, [jendeak esango du] ez dago quiola nescacha bati bururic ausitzea liburuguiñen: asco duela gorua, naiz jostorratza zucen erabiltzea ‘people might say it is not appropriate for a girl to rack her brains to write a book, because how to properly spin and saw is all she needs to know’.

Reproduction of the original cover. Courtesy of Jabier Kalzakorta.

With the publishing of the book of fables, Vicenta Moguel demonstrated that apart from being a brilliant writer she was a daring woman who lived well ahead of her time. The fables were said to provide most useful life lessons for rural folk, children and youth of the Basque Country in particular, as the full title of the book indicates: Ipui onac, ceintzuetan arquituco dituzten euscaldun necazari, ta gazte guciac eracaste ederrac beren vicitza zucentzeco.

Her literary production did not end with the mentioned publication. Once married and living in Bilbao she created, over the first two decades of the 19th century, some genuine Christmas songs to be sung in church. The songs could well have been written by an anonymous hand, for the author’s signature reads: emacume batec ateriac ‘published by a woman’.

Jabier Kalzakorta – Full member of the Academy of the Basque Language and professor at the University of Deusto

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa