Basque ethnography at a glance

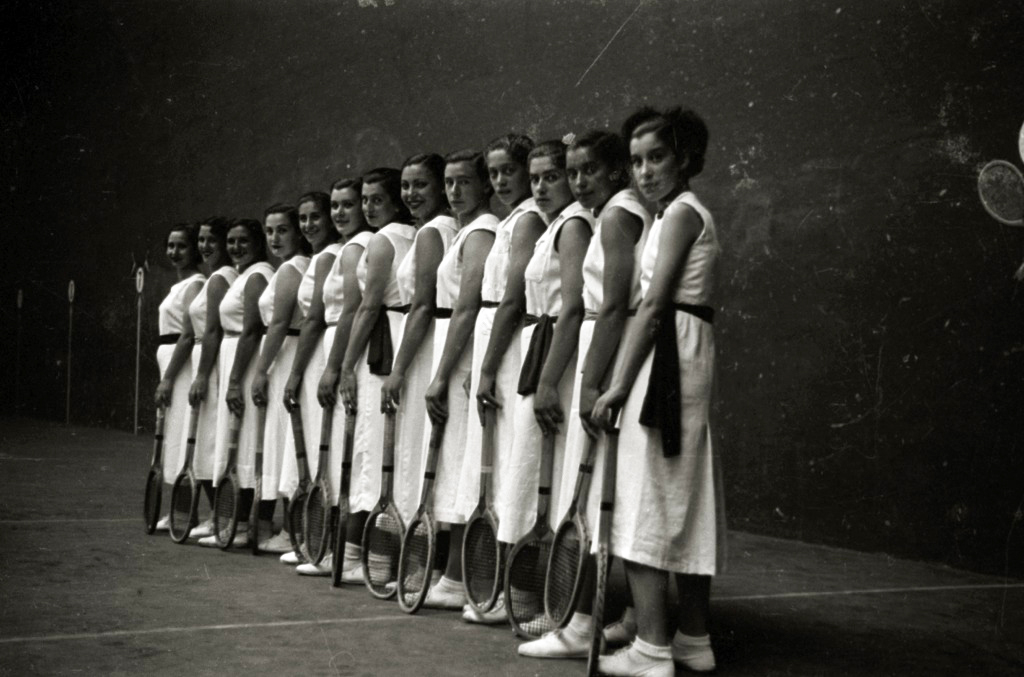

Group of women racket players. Gros Fronton in Donostia, 1938. Pascual Marín. Kutxateka.

Some time ago the Euskal Herria Museum in Gernika presented the exhibition “Emakumea eta Euskal Pilota. Mujer y Pelota Vasca [Woman and Basque pelota]”, which has been shown in different locations in Bizkaia. It is an interesting research work intended to rethink the role of women in Basque pelota, or pilota, by reminding us of the forgotten presence of female racket players, or raquetistas, in ball courts worldwide throughout the 20th century while giving due recognition to their contribution.

Various variations of pelota have been played around the world, the Basque Country being where it has taken a higher profile. From its beginnings it has been perceived as more of a man’s sport, but yet women also have been involved in all areas and categories of the game since remote times, specializing and making their greatest achievements in the racket modality, or raqueta.

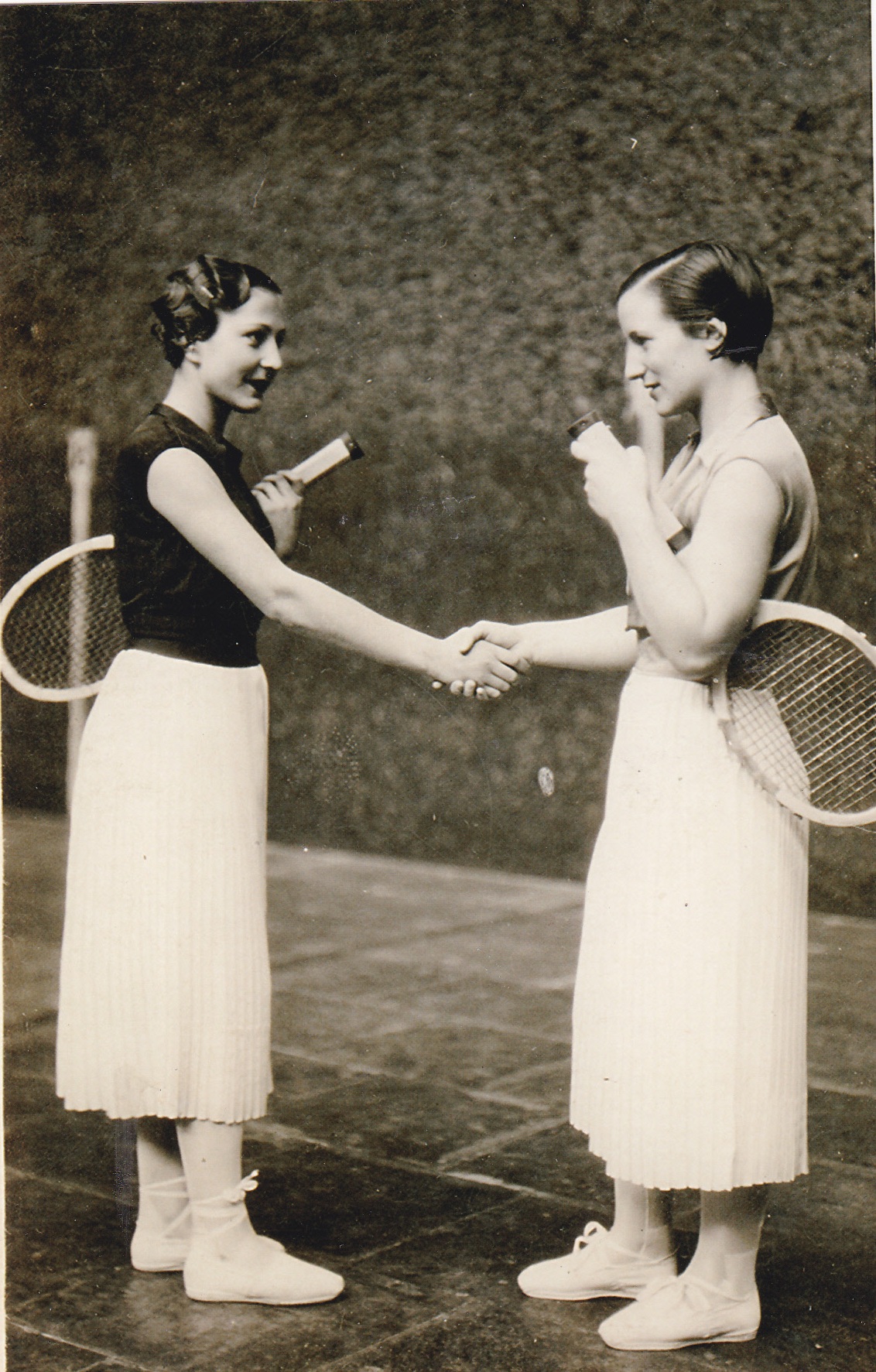

The racket game was practiced for more than sixty years (1917–1980) in Spain and America. In its origins important innovations were introduced in the courts and the equipment. Tennis balls were replaced by leather ones, not as heavy as those used in handball, approximately 50 to 70 g in weight, and these in turn required more solid and longer rackets than tennis rackets, with a narrower head. There were also changes on the clothing of players over the years, most of them in the length of the skirts: raquetistas of the 1920s and 1930s wore skirts down to their calves; in the 1940s General Moscardó ordered ankle-length skirts be worn, which made the practice of sport more difficult; skirts rose to just below the knee in the 1950s and subsequently became gradually shorter as a faster and more dynamic game developed.

Post-match handshake between racket players at Madrid Fronton. Catalogue of the exhibition.

The enduring success of the discipline is largely attributable to the magnificent squads of women pelotaris assembled by the court managers. The majority of these young women were scouted in Basque towns and cities with a strong pelota tradition; paradoxically, however, this variation of pelota was played little in the courts of the Basque Country. The game produced many renowned players who deserve to be remembered: Eugenia Iriondo «Eibarresa»; Carmen Sánchez «La Bolche»; M.ª Antonia Uzcundu «Txikita de Anoeta»; Agustina Otaola; Eladia Altuna «Irura»; M.ª Luisa Alberdi; M.ª Carmen Lasagabaster «Amaia»; Gloria Agirre «Txikita de Aizarna»; Lucía Areitoaurtenea; the Beraza (Julita, Mari and Milagros) sisters; Conchita Bustindui; Olga Cazalis; M.ª Luisa Senar; Rosa Soroa; Miren Uzkundun «Asteasu»; Justina Arenaza «Vasquita I» and her sister María «Vasquita II». Although the best and most numerous racket players were Basque, they shared the court with players from Valencia, Logroño, Madrid, Barcelona or Mexico.

Many of the pelota courts that opened in the early years of the 20th century were designed or adapted for the game of racket pelota, with a length of around 30 m, resulting in the development of a faster and more spectacular game. The first racket court opened in Cedaceros Street in Madrid in 1917. It was indeed in Madrid where the racket game found its greatest following and where most courts opened. Barcelona also had several leading venues. The only frontons in the Basque Country to host raqueta matches were the Euzkel-Jai in Bilbao and Gros Fronton in Donostia. In America the game enjoyed overwhelming success and drew large crowds of followers to frontons such as the Habana-Madrid in Cuba or the Metropolitan in Mexico.

As a whole culture grew up around the game of raqueta, the popularity and skill of the raquetistas were reflected in the press, literature, cinema or television of the time: novels such as Chiquita de Bilbao by Luis Antonio de Vega Rubio, the film noir Apartado de correos 1001 [Post office box 1001] directed by Julio Salvador in 1950, or the documentary El ocaso de las raquetistas [The downfall of the racket players] made by the journalist Carmen Sarmiento in 1978.

The last raqueta match was played in Madrid on 17 July 1980. Thereafter both the sport and its players suffered a decline in popularity and practically fell into oblivion.

Arantxa Pereda – Curator of the exhibition

Translated by Jaione Bilbao – Ethnography Department – Labayru Fundazioa